Archives

AND MORE...

Turkish Piece of Work

_____________________

Those 'Secret' Relationships

_____________________

Obama's Turkeys

_____________________

Axis of Something

_____________________

Turkeys

_____________________

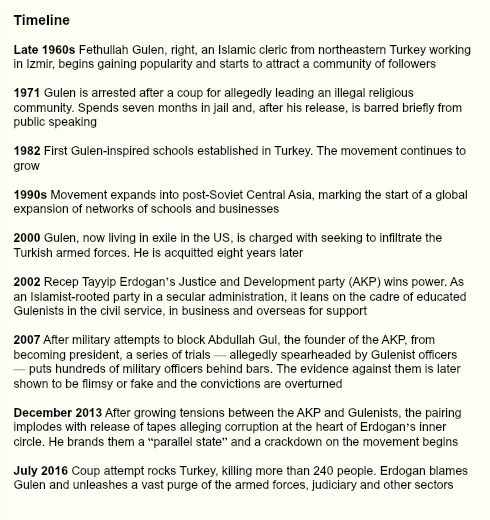

September 12, 2016

Battle Of The Islamists

Coups, purges, crackdowns, witch-hunts, paranoia and secretive movements are all words to describe Turkey’s politics today, especially since the attempted coup d'état in July 2016 (see below).

The main figures in this Islamist drama are Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, an “increasingly paranoid authoritarian” and Fethullah Gulen, an ageing Islamic cleric exiled in Pennsylvania.

Erdogan has accused Gulen and his secretive religious movement of masterminding July’s audacious coup attempt that left more than 240 people dead.

Since the coup attempt, Turkey’s government led by Erdogan has overseen a vast purge that’s raised alarms in the west. More than 100,000 people have been dismissed or suspended from their jobs in the military, police, judiciary, civil service and schools. At least 40,000 have been detained. The crackdown has prompted comparisons with Stalin’s Russia and McCarthy-era America.

“The concept of a shadowy religious network weaving its tentacles into a state may sound like the plot of a Dan Brown novel,” writes Laura Pitel below. “But, as the columnist Asli Aydintasbas wrote in an opposition newspaper recently: ‘What sounds like fantasy to westerners is our reality.’ “

For a better understanding of what Turkey is experiencing today, read the piece below.

Financial Times | September 11, 2016

Turkey: Gulenist Crackdown

Even critics of the secretive movement, accused of coup attempt, fear its suppression is going too far

By Laura Pitel

Professor Tayfun Uzbay

It is hard to imagine a more unlikely pimp than Professor Tayfun Uzbay. The silver-haired scientist has a quiet manner and speaks in sentences as neat as the rows of certificates that line his office wall. But in 2012, the pharmacologist was arrested and accused of using prostitutes to extract secrets from military officers.

The allegations were fiction, he says. He insists he had never met the women and knew few of the officers he had allegedly targeted. He spent a lonely nine months in prison before being released in February 2013. Three years later, he and all 356 others ensnared in what became known as the Izmir espionage case were acquitted.

Prof Uzbay, a colonel who before his arrest headed his department at Gulhane Military Medical Academy in Ankara, is cautious about leaping to conclusions about his ordeal. “I try to speak about this as a scientist,” he says. “I talk based on evidence and fact.”

Yet his story, and those of other military doctors in Turkey with similar experiences, suggest the hand of the secretive religious movement led by Fethullah Gulen, an ageing Islamic cleric exiled in Pennsylvania. Mr Gulen stands accused of encouraging his followers to infiltrate the Turkish state over several decades. And, while he vigorously denies it, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkish president, accuses the former imam of masterminding July’s audacious coup attempt that left more than 240 people dead.

The concept of a shadowy religious network weaving its tentacles into a state may sound like the plot of a Dan Brown novel. But, as the columnist Asli Aydintasbas wrote in an opposition newspaper recently: “What sounds like fantasy to westerners is our reality.”

In Turkey, the Gulen movement is often depicted as a wealthy quasi-religious cult with a thirst for power. Its supporters are accused by the government and the secularist opposition of infiltrating the state and using wiretapping, blackmail and fraud to eliminate rivals and promote supporters.

But Mr Erdogan has had difficulty convincing the rest of the world of Mr Gulen’s role in a coup attempt that came close to claiming his life. He is hampered partly by his image in the west as an increasingly paranoid authoritarian. And over the years the movement has successfully cultivated a reputation for promoting quality education, interfaith dialogue and a tolerant vision of Islam.

“Now it’s a lobbying war,” says Ezgi Basaran, a former editor of the newspaper Radikal who has investigated the movement. “In Washington and in London I know that Gulenists have been working for years [to gain good PR]. They are making their case much more easily than the authoritarian Erdogan.”

The story of Prof Uzbay, and those of others like him who have worked at military hospitals, helps explain why many in Turkey detest the movement — and why they believe it could be willing to launch an attempted putsch.

Claims of infiltration

Since the coup attempt, the Turkish government has overseen a vast purge that has raised alarms in the west. More than 100,000 people have been dismissed or suspended from their jobs in the military, police, judiciary, civil service and schools. At least 40,000 have been detained. The crackdown has prompted comparisons with Stalin’s Russia and McCarthy-era America.

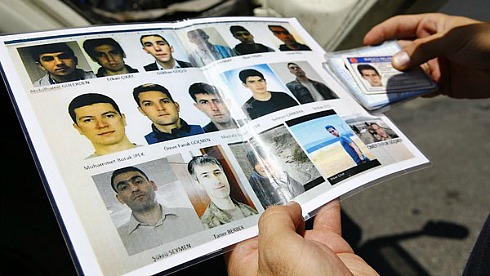

Police officers conducting road checks hold lists of soldiers suspected of involvement in coup attempt. Photo: Getty

Among the most eye-catching details was the issuing of arrest warrants for 98 staff at Prof Uzbay’s former hospital in Ankara. Gulenists cited it as proof of a witch-hunt. What kind of state accuses doctors of trying to launch a coup?

But, on top of the case of Prof Uzbay, four current and former staff told the Financial Times that they believe Gulenists had in fact infiltrated Turkey’s network of military hospitals. They echoed claims by a senior Turkish official that the institutions were “crucial” to the movement’s efforts to permeate the wider armed forces.

“If a person wants to be a soldier or a pilot, he or she must be fully healthy,” says Nurettin Yiyit, a thoracic surgeon who holds the rank of major at Istanbul’s Haydarpasa military hospital. “The military hospitals have a very big role in shaping the army.”

The doctors painted a picture of unfair promotions, harassment and tampering with test results that became common from the mid-2000s as the movement’s foothold grew stronger.

Ilhan Asya Tanju, a paediatrician, is one of two doctors who said that they left their jobs after facing a sustained Gulenist campaign. He claims that, from around 2006, he and colleagues at Haydarpasa hospital were harassed by anonymous Twitter accounts. He saw confidential medical information about opponents of the movement appear in the Gulenist press.

In 2014, he says he learnt via a colleague that he had no chance of a promotion despite plentiful experience. The same year, he was told that he and his family must relocate to a far-flung eastern province — an attempt, he believes, by Gulenists to make his life difficult. He resigned.

The doctor, who held the rank of major, claims the Gulenists saw him as an obstacle to their plans to gain control of the institution’s levers of power.

Dr Yiyit became convinced in about 2012 that Gulenists were seeking to manipulate the system after noticing evidence of tampering on doctors’ performance grades and with test results for young military recruits. He says he faced pressure to leave but resisted and began warning army superiors, politicians and intelligence officers about the Gulen movement.

The FT confirmed that he complained to at least one senior figure in Mr Erdogan’s Justice and Development party (AKP) in 2014 and has seen a letter from the chief legal adviser to the head of the armed forces acknowledging receipt of a complaint the same year.

While aspects of the doctors’ accounts can be verified, it remains almost impossible to prove that the allegations were a Gulenist scheme rather than the result of personal grievances or a broader culture of bullying. As Dr Yiyit himself admits, one of the biggest problems is that it is rarely possible to be sure whether someone is or is not a Gulenist.

Since its inception in the late 1960s, the movement has placed great importance on secrecy. Even before the coup attempt, supporters seldom admitted to following Mr Gulen. In the military, Gulenist officers are said to drink alcohol — forbidden by Islam — as a way to mask their faith. Mr Gulen’s followers say such tactics were essential in a country where state secularism had led to past persecution. Critics say the secrecy fuels suspicions of an ulterior motive.

Government supporters at an Istanbul rally after the failed coup. Photo: AP

Either way, the movement’s clandestine nature means that those convinced of its darker side base their conclusions on circumstantial evidence such as similarities in the modus operandi of Gulenist police and prosecutors, campaigns by Gulenist-affiliated media and the swift retribution doled out to those who dared to criticise the movement.

Prof Uzbay’s arrest fitted a pattern seen in similar cases, including an anonymous tip off that led to the “discovery” of a hard disc containing the “evidence” against him. Before he had even appeared in court, his detention made the front page of Zaman — the Gulen movement’s flagship title until it was seized by the state in March.

Now, dozens involved in bringing the Izmir case to court are themselves accused of being Gulenists and are facing trial on charges of forging evidence.

A partnership falters

For years the Gulen movement was bound in a marriage of convenience with Mr Erdogan’s AKP, which has dominated Turkish politics since 2002. The AKP harnessed Gulenist manpower in the police, prosecution service and judiciary to counter the threat posed to a party rooted in political Islam from the staunchly secularist establishment.

The danger was real. In 2007, the military tried to stop AKP co-founder Abdullah Gul from assuming the role of president. The ruling party fought back. Over the years, hundreds of military officers were jailed on accusations of plotting a coup after two major trials, known as Ergenekon and Sledgehammer, which were largely orchestrated by Gulenists. But many of the cases eventually crumbled when much of the evidence was exposed as fabricated. Convictions were later overturned.

From 2009, a party official says the AKP-Gulenist relationship grew strained until, in 2013, it imploded. Leaked recordings of telephone conversations, allegedly obtained by Gulenists in the police intelligence unit, seemed to show brazen corruption in Mr Erdogan’s inner circle. He responded by accusing the movement of building a “parallel structure” within the state and by launching a crackdown on its activities.

Since the July coup attempt, senior AKP figures have sought to cast the party as a naive but sincere victim of what turned out to be a calculating cult. Mr Erdogan has asked for forgiveness from God for the error. Given the history, this has left Mr Erdogan’s opponents distinctly unimpressed.

The belief that the Gulenists directed unfair trials and sabotaged careers helps explain the hatred many Turks feel toward them. But even if it could be proved that Gulenists were behind the imprisonment of Prof Uzbay or the manipulation described by other military doctors, it does not necessarily follow that they led the coup attempt.

In the tumult since July, even some of the movement’s harshest critics are urging caution. “I am questioning all the evidence coming from the government side,” says Ms Basaran, the former Radikal editor. “I know it can be faked.”

Turkey is adamant that the putsch was ordered by Mr Gulen. He has protested his innocence, though he has left open the prospect that some sympathisers could have betrayed his ideals.

In support of their case, Turkish officials hold up Hulusi Akar, the Turkish armed forces chief held hostage on the night of the coup attempt, who reportedly told prosecutors that one of his captors offered to help him contact Mr Gulen. They also point to confessions of alleged plotters. But such testimonies have been overshadowed by accusations that detainees have been subjected to beatings and torture.

Fethullah Gulen at home in Pennsylvania. Photo: Reuters

Turkey has yet to provide sufficient evidence for the US to agree to its demand for the extradition of Mr Gulen, straining ties between the Nato allies.

Gareth Jenkins, an Istanbul-based analyst and expert on the Gulen movement, says the Turkish government’s insistence that the plot was purely a Gulenist affair is “problematic” given the scale and scope of the plan. More than 40 per cent of admirals and generals have been accused of being involved.

“They clearly haven’t yet got a smoking gun,” Mr Jenkins says. “If they had, we would have heard of it.”

Some of those who took part in the coup attempt were hardline secularists or “just hated Erdogan”, he believes.

That view was echoed by two of the doctors interviewed, who said they were certain some of their arrested colleagues were not Gulenists. Several balked at the overhaul of the armed forces announced after the failed putsch — including a decision to bring all military hospitals under civilian control.

The speed and breadth of the crackdown have caused alarm among human rights groups and opposition parties. Turkish officials say authorities are working from lists of suspects prepared before the coup attempt. But the criteria appear sweeping. Mr Erdogan has encouraged citizens to inform on one another. Government critics with no apparent links to the Gulen movement have been detained. People who simply admire Mr Gulen’s teachings are terrified of being unjustly accused.

Turkey’s prime minister, Binali Yildirim, insists that all suspects will be given a fair trial. But, having fallen out with almost everyone in Turkey, the Gulenists have few friends.

Moderates are calling for restraint to avoid destructive cycles of recrimination such as those that Gulenists themselves were accused of spearheading.

Despite his ordeal, Prof Uzbay, who is now at Uskudar University in Istanbul, is one of them. “I am against this being a witch-hunt,” he says. “Many innocent people may be labelled guilty. I’ve been through this. It was hard. I do not want others to go through the same thing.”

Original article here.

Log In »

Notable Quotables

"Mr. Netanyahu is one of the most media-savvy politicians on the planet. On Friday he appeared live via video link on 'Real Time with Bill Maher,' taking the host’s alternately sardonic and serious line of questioning with gazelle-like alacrity."

~ Anthony Grant, jourrnalist who has written for many major newspapers and worked in television at Paris and Tel Aviv, interviewing former PM Benjamin Netanyahu on Monday, at the outset of Mr. Netanyahu's new book (more here).